|

ROSALIND WATES

is one of those born mosaicists who was not born a mosaicist. Which

is to say, she took a foundation course at Carlisle College of Art

and Design, studied decorative arts at City and Guilds, and for

several years worked in various media. But came a day when Mr. and

Mrs. Michael Caine decided She is always ready to experiment. You may recall her variation on the reverse method (see Mosaic Matters no.2), and when I visited her studio she was using the tricky technique known as "double reverse" for a 3« x 2 metre wall mosaic, a map of Petersfield. The detail, which included lettering, was so fine that she felt she needed to see directly what the result would be. So she stuck the pieces face up onto paper; then stuck paper on the top, lifted the finished mosaic, removed the underneath paper, and installed the mosaic on site in the usual way. Not an easy technique when the tesserae are small, but it worked well.

Her magnum opus to date was created for her native Cumbria (she was bred in Kendal). You may have heard of the Theatre In The Forest, at Grizedale. Nearby you find many open-air sculptures, ranging from giants to a wooden xylophone. In 1992 Rosalind was awarded an artist-in-residency. The brief was to create a mosaic using natural stone gathered from the locality. The site was on a flat part of a hillside overlooking Grizedale Valley. She started by defining her mosaic as "in the landscape, of the landscape, about the landscape". It was to be a twenty-foot diameter circle, and the first job was to lay an eight-inch deep concrete foundation. The next was to look for the stone... But I'll let her tell her own story. "I started to drive around the local slate quarries in search of materials. I wanted to make the mosaic with off-cuts from the quarry waste heaps, and had a glorious time creating my 'palette' from what I found. It is a wonderful thing to find yourself halfway up Coniston Old Man as the sun rises, a sack over one shoulder, picking around the foot of some vast quarry in search of 'badger' grey, or dark Coniston Green pieces. Sometimes there was snow, which was awkward when hunting for pieces of quartz! The quarry owners were without exception helpful, and one of them taught me how to split slate. The greatest surprise of the project lay in the variety of colours that came out of the Lake District hills. I had expected to find dark green, light green, and varying shades of grey - a meagre palette compared to the marble riches of Italy. I was unprepared to find bright orange (refuse from copper mines), yellow, a whole range of reddish-browns, and most astonishing of all (especially when placed next to the green slate) some fragments of a rich maroon slate. The latter, it emerged, were brought from Welsh quarries to be cut in the Lake District. The lure of gold had to be resisted in the form of iron pyrites, glinting among the rocks. The pieces were set in a bed of mortar two inches thick. To enable me to reproduce the design accurately, I invented a technique using two-inch thick polystyrene cut-outs of the principal motifs. Having laid them in place upon the foundation, I filled them with mortar, and they formed an accurate guide for laying the mosaic. When the mortar had set, the polystyrene was broken off and the surrounding area filled. Where possible I used slate pieces as found, but it was necessary to shape many of them. For the smaller cut pieces I used a hammer and hardie. The large pieces which form the background were rejected roofing slates. These were shaped with a slater's knife and bench. The mosaic was started in late golden summer. It took nearly three months to complete. Through the succeeding very wet autumn my assistant and I learned new skills, and discovered unforeseen powers of endurance. Many people visited the site, and their interest and enthusiasm spurred us on. Even so, it was well into December when the mosaic was finished. The trees were bare, the robins more aggressive, and meadow had turned to mud. Many of the sculptures at Grizedale reflect the passing of time, the transience of the seasons. Made from organic materials, they exist for a while, then decay naturally back into the ground; a planned mortality which is an essential part of their concept. The Grizedale Mosaic is different. As the Romans left their mark, so have I left mine: a message to future generations saying that we don't just care about wealth, power, and the materialistic things of life. Beyond all that, there's a part of us that is still claimed by the wilderness." Slate also appears in Rosalind's latest commission. It is a mural to celebrate the town of Workington, Cumbria. Such things as cranes and coal mines will be framed within a sail-shaped mosaic; and it will be made from slate and smalti. Dream commission? Another hillside mosaic - a lifesize Harrier Jumpjet. Fingers crossed. (You can get in touch with Ms. Rosalind Wates, Malberet, Bar Lane, Owlswick, PRINCES RISBOROUGH, Bucks. HP27 9RG ws phone/fax 01844 342 005 mobile 0802 790 907

|

All

content is copyright of © Mosaic Matters and its contributors.

All rights reserved

Mosaic

Matters is:

Editor: Paul Bentley

Web Manager/Designer: Andy Mitchell

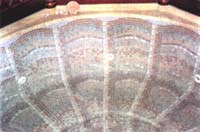

they wanted a mosaic jacuzzi; a friend recommended

Rosalind and, as she puts it, "I plunged into the unknown". She's

not afraid of a pun, you gather, nor of a challenge, either. The

jacuzzi was an odd, curved shape, and so she decided to work direct,

with her design based on the idea of a shell. The customers were

delighted with the result.

they wanted a mosaic jacuzzi; a friend recommended

Rosalind and, as she puts it, "I plunged into the unknown". She's

not afraid of a pun, you gather, nor of a challenge, either. The

jacuzzi was an odd, curved shape, and so she decided to work direct,

with her design based on the idea of a shell. The customers were

delighted with the result.

Rosalind uses many materials for her mosaics: stone,

glazed or unglazed ceramic, as well as the usual smalti and vitreous

tesserae. She would never use vitreous for a floor mosaic, I learned,

ever since they failed her Dropped Brick Test, but she has discovered

gold and silver tesserae you can use in a floor. They are made the

opposite way from ordinary gold, in that the thickness is on top.

Rosalind uses many materials for her mosaics: stone,

glazed or unglazed ceramic, as well as the usual smalti and vitreous

tesserae. She would never use vitreous for a floor mosaic, I learned,

ever since they failed her Dropped Brick Test, but she has discovered

gold and silver tesserae you can use in a floor. They are made the

opposite way from ordinary gold, in that the thickness is on top.

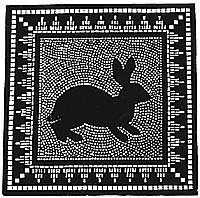

The mosaic has an unashamedly environmental theme. Five

indigenous mammals, frozen mid-movement and turned to stone, follow

each other around the central sun. Balancing this fiery heart is

another element essential to life: a river motif, which forms a

border to the mosaic. The arrangement of this 'circus' owes much

to the Romans, who discovered many of the best solutions to the

problem of dividing and using space on floor areas. They too used

animals as subjects for their art; sometimes domestic, sometimes

wild, and sometimes strange, barely discovered creatures from the

far-flung corners of their Empire. The sense of discovery in their

world is replaced in ours by a sense of loss. As we destroy our

landscape and the creatures that live in it, so we are beginning

to value them in an entirely new way. We are learning to hold dear

the natural - or even unnatural - woodland, the unpolluted streams,

and the ever more elusive otter, deer, fox, hare and badger featured

in the mosaic.

The mosaic has an unashamedly environmental theme. Five

indigenous mammals, frozen mid-movement and turned to stone, follow

each other around the central sun. Balancing this fiery heart is

another element essential to life: a river motif, which forms a

border to the mosaic. The arrangement of this 'circus' owes much

to the Romans, who discovered many of the best solutions to the

problem of dividing and using space on floor areas. They too used

animals as subjects for their art; sometimes domestic, sometimes

wild, and sometimes strange, barely discovered creatures from the

far-flung corners of their Empire. The sense of discovery in their

world is replaced in ours by a sense of loss. As we destroy our

landscape and the creatures that live in it, so we are beginning

to value them in an entirely new way. We are learning to hold dear

the natural - or even unnatural - woodland, the unpolluted streams,

and the ever more elusive otter, deer, fox, hare and badger featured

in the mosaic.