|

SISTER MARIA AND THE MONASTERY OF JOHN THE BAPTISTby Paul Bentley

A little history before we visit her monastery. Like most people in our island, I'd been brought up to think that our civilisation started with the Greeks, continued with the Romans, enter Christianity, then came The Fall Of The Roman Empire (476 A.D.), the Dark Ages, the Middle Ages, and so on. What no-one told me was that the Roman Empire did not fall in 476. The West fell to the barbarians, certainly. Goths, Vikings, all that. But the Eastern half of the Empire, centred on Constantine's "New Rome" (alias Constantinople and Istanbul), carried on for another thousand years, till the capital finally fell to the Turks in 1453 - all in all Byzantium lasted for much longer than the original Roman Empire did. And for half that time, until the Middle Ages really got going, the Byzantine Empire was Christian civilisation. And it was superb. And to the end the citizens called themselves Romans.

Although Byzantium fell, the Byzantine ("Orthodox") Church survived, and so did Byzantine religious art, mainly in the form of what we call icons, and that's the tradition that Sister Maria and her colleagues work in. "Icon" is simply the Greek word for image (Christ is the icon of the invisible God, says St. Paul), though it's usually taken to mean a wood panel religious painting used by Orthodox Christians.

The Monastery of St. John the Baptist is in the village of Tolleshunt Knights, near Maldon in Essex. It is a community for both monks and nuns, founded in the 1950s by a remarkable man, Archimandrite Sophrony. He was originally a painter, born in Tsarist Russia, who lived through the First World War and the Revolution, and emerged with a longing to devote his art to exploring the nature of Divine reality. He emigrated to Paris via Italy, painted, then studied theology for a while, until he decided that he had a vocation to become a monk. So he went to Mount Athos; his spiritual director there was Staretz Silouan. Years later, he came to England and - naturally - the monastery he founded was to be decorated according to Byzantine tradition. Work started in the Refectory, which was decorated with murals, using oil and turpentine on plaster, to look like Byzantine fresco. Sister Maria, who had studied iconography in Paris with Leonid Ouspensky and Fr. George Drobot, was one of those who helped carry on the work.

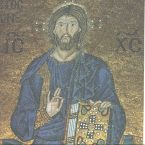

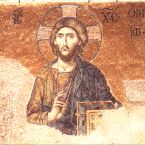

The whole aim of the icon - whether in paint or mosaic - was and is to use physical means to involve the viewer with the spiritual, the super- natural. The icon is the door to another world. It is not "naturalistic art"; on the contrary, various techniques are deliberately employed to remind the beholder that the icon is a "silent teacher". For instance, in scenes, Western linear perspective, with a vanishing point in the far distance, is not used. (Indeed, the background is often plain gold.) Rather, multiple perspective is used, or converging perspective, where the vanishing point (better, "absorbing point") is the viewer... Body language is important - a hand pointing to the heart, or the fingers of a hand forming ICXC, the Greek letters for Jesus Christ. Passionate human emotions like anger and anguish are normally excluded - the overall goal is a serene, even solemn, concentrated stillness and inwardness, akin to Gerard Manley Hopkins' "instress".

Take three mosaic Christs, seated, clad in blue and gold, right hand raised in blessing, dating from the 6th (Apollinare Nuovo), 11th and 13th centuries (Zoe and Deeisis panels in St. Sophia, Constantinople). The first is naturalistic, a stern judge; you sense a powerful body beneath the robe. The second is ultra-linear, two-dimensional, flat, almost abstract; there's little sense of a real body. The third is much more naturalistic again, but this time Christ is a compassionate redeemer. And it's that late Byzantine style, the Palaeologan, that Sister Maria prefers as a model. |

All

content is copyright of © Mosaic Matters and its contributors.

All rights reserved

Mosaic

Matters is:

Editor: Paul Bentley

Web Manager/Designer: Andy Mitchell