|

NEW MOSAICS IN WESTMINSTER CATHEDRAL – JUNE 2003

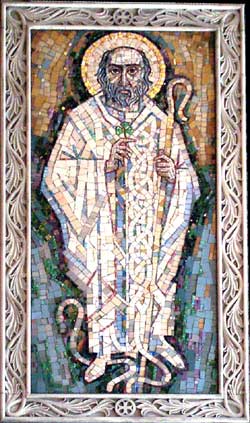

Then around ten years ago there came a revival of the genuine article, and in the Cathedral something stirred - the Art and Architecture Committee decided to commission a panel of St. Patrick. They chose Trevor Caley, an experienced mosaicist, who produced a masterpiece. Next they wanted a panel of St. Alban, and this time commissioned Chris Hobbs, a self-taught painter, sculptor, stage and screen designer but not, as it happened, a mosaicist. Now the interesting thing about this committee is that it fields

no-one with professional knowledge of mosaic-making; so what you

have here is a committee which knows little about mosaic commissioning

an artist who knows little about mosaic to design a mosaic. Not

on the face of it a recipe for success. In fact the Alban panel

turned out well; Hobbs did his research and chose to model the face

on second-century Egyptian coffin portraits. The result was a suitably

Early Byzantine-style saint, and the painterly, almost pointilliste,

design was turned into a mosaic by Tessa Hunkin of Mosaic Workshop. For there are two points to be debated, and the first is – is it really a good idea to ask a non-mosaicist to design a mosaic? There have been disasters in the past; for example, Chagall's design for a mosaic in the Knesset building in Jerusalem. He produced a rough, blurry sketch which completely ignored the fact that mosaics are made of small, hard chunks of glass, ceramic and stone. Centuries earlier Tintoretto and Veronese were equally thoughtless when painting cartoons for mosaics in San Marco, Venice. Mosaic is a medium which makes special demands and is at its best

when strong and simple, with a limited palette. The chances are

that artists who have been mosaicists for years will produce more

effective work than a tyro, because from the start they will be

thinking mosaic - the concept and the medium will be one. Mosaicists

work faster too; Tessa Hunkin found that it took a long time to

choose a tonally blended mosaic palette On the other hand Hobbs clearly did his homework; coffin portraits and icons were the inspiration for the Family, and Jesus' clothes have gold highlights in true Byzantine fashion. What's more, in the design for the workers' wall we can see both eyes of everyone portrayed. Hobbs got that right by instinct, not research; in Byzantium mosaic saints were considered "virtually present" in the church; hence the wicked were portrayed in one-eyed "not present" profile. Further, it was presumably Hobbs's work in theatre which made him aware that mosaics have to read close up and at a distance. So do we conclude that a painter & mosaicist are the acceptable (though slow and expensive) equivalent of a mosaicist working on her own? Is Hobbs & Hunkin's Alban panel as good as Caley's Patrick panel? Then there's the question of style. Suppose we say that Hobbs's designs are pastiche. Why shouldn't they be? Sondheim composed pastiche for Follies and all people said was, "They don't write songs like that any more". What, pray, is the difference between pastiche on the one hand, and the renaissance of a style on the other? Between Follies and Stravinsky's neo-Classical Rake's Progress? Between Hobbs's designs and Anrep's neo-Early Byzantine mosaics in the Cathedral's Blessed Sacrament chapel? Come to that, why does pastiche have a bad name? Presumably because it is mere imitation, for which a distinctive artistic personality is not required; the job is to think yourself into a given period and reproduce the style. We assume the pasticheur's heart isn't in it, only the head. But suppose the heart was involved? Suppose we could lay our hands on artists who not only think but feel Byzantine? They do in fact exist; they are icon makers, Christian artists who with skill and piety reproduce traditional Byzantine subject matter in the traditional way.

So one asks: has Hobbs come up with skilled pastiche or inspired re-creation? And does it matter? Whatever the answers, the committee are clearly happy: they have asked Hobbs to design the Thomas Becket chapel next… Paul Bentley (This article was first published in the Catholic Herald on 13

June 2003, with photographs by Andy Mitchell.) |

All

content is copyright of © Mosaic Matters and its contributors.

All rights reserved

Mosaic

Matters is:

Editor: Paul Bentley

Web Manager/Designer: Andy Mitchell

Cathedrals

are not built overnight but Westminster Cathedral came close: the

huge Byzantine-style building was up and running in just eight years

(1895 to 1903). Then there was the little matter of interior decoration

- marbling the lower half and mosaicing the upper half - and at

that point things slowed down. By the nineteen-sixties the marbling

was just about finished and half the chapels had their mosaics.

After which came The Great Pause. Not an inch of mosaic for the

next thirty years. Just as well, because in those decades British

mosaic lost its soul; ignorant cowboys slapped acres of the stuff

on assorted public buildings, and true mosaic artists were rare

birds.

Cathedrals

are not built overnight but Westminster Cathedral came close: the

huge Byzantine-style building was up and running in just eight years

(1895 to 1903). Then there was the little matter of interior decoration

- marbling the lower half and mosaicing the upper half - and at

that point things slowed down. By the nineteen-sixties the marbling

was just about finished and half the chapels had their mosaics.

After which came The Great Pause. Not an inch of mosaic for the

next thirty years. Just as well, because in those decades British

mosaic lost its soul; ignorant cowboys slapped acres of the stuff

on assorted public buildings, and true mosaic artists were rare

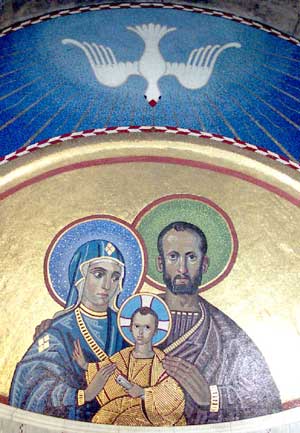

birds. The committee then asked Hobbs to come up with a design for a whole

chapel, that of St. Joseph. For the altar wall Hobbs decreed a Holy

Family with the Dove above; for the wall opposite, workers building

the cathedral; and for the ceiling, a basket-type pattern, as of

a manger. It's Tessa Hunkin's version of the Holy Family and Dove

which has just been installed for all to ponder.

The committee then asked Hobbs to come up with a design for a whole

chapel, that of St. Joseph. For the altar wall Hobbs decreed a Holy

Family with the Dove above; for the wall opposite, workers building

the cathedral; and for the ceiling, a basket-type pattern, as of

a manger. It's Tessa Hunkin's version of the Holy Family and Dove

which has just been installed for all to ponder. equivalent

to the colour range in Hobbs's design - "It's a hundred times

more complicated, using someone else's painting." And time

costs money.

equivalent

to the colour range in Hobbs's design - "It's a hundred times

more complicated, using someone else's painting." And time

costs money. Yet

we hold Anrep's Blessed Sacrament mosaics in higher regard than

modern icons. Why? Because he contributed so much that was uniquely

and recognizably his, without making the mosaics more about him

than about the Eucharist. He took elements of the Early Byzantine

style and re-worked them, as Stravinsky did with elements of the

Classical style in Rake's Progress. Both artists struck a balance

between imitation and their own idiom. They re-created. Superbly.

Yet

we hold Anrep's Blessed Sacrament mosaics in higher regard than

modern icons. Why? Because he contributed so much that was uniquely

and recognizably his, without making the mosaics more about him

than about the Eucharist. He took elements of the Early Byzantine

style and re-worked them, as Stravinsky did with elements of the

Classical style in Rake's Progress. Both artists struck a balance

between imitation and their own idiom. They re-created. Superbly.