|

WHAT ISLAM TOOK FROM BYZANTIUMOne of the many effects of the terrorist attack in Madrid in 2004 was to prompt reflection on the period when Spain was mainly Muslim and was the principal channel through which Islam influenced the West. Lord Carey, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, reminded us that we are indebted to Islam for such things as Greek thought and the calculus. Indeed Western mathematics, science, medicine, music, philosophy and even theology have much to be grateful for. On top of that Islam gave us pepper and paper and the guitar. But what few realise is the huge influence that others had on Islam. Sassanid Persia, for instance, and above all the Empire of Byzantium.

Byzantine influence on Islam was inevitable. When Mohammed died in 632 Arab armies charged north out of the desert into a superb, sophisticated Christian civilisation, the half of the Roman Empire which had not been subject to Decline and Fall. Quite the contrary. The Arabs knew that and sought not merely to conquer but to imitate and surpass. But first they had to learn. Not about war on land - Byzantium had its work cut out coping with their fast and furious tactics. Probably the only thing the Arabs adopted was the Byzantine practice of using cunning to win battles, encouraging the enemy to desert or switch sides.

Running even a part of someone else's empire takes practice, so it's not surprising that to begin with the Muslim invaders were content to let Christians continue administering countries like Syria and Egypt. Early Muslim coins were copies of Byzantine coins but with the arms of the Cross of Calvary removed, leaving a pole on a pedestal.

Where art and architecture were concerned it took a couple of centuries but at length Muslims succeeded in uniting techniques and themes from their conquered lands and recasting them into forms that breathed the spirit of Islam, and which in the opinion of many far surpass the originals. It is certainly true that Byzantium in turn adopted certain Muslim developments in art and architecture. But even as late as the tenth century the Caliph of Cordoba asked the Emperor to send a mosaicist to work on the Great Mosque there. The man duly arrived equipped with tons of cubes and taught a group of locals how to mosaic. What's more, it seems that the Muslim palaces of southern Spain, such as the Alhambra, were descendants of the Great Palace in Constantinople, now alas no more. On the other hand, in the twelfth century a building in the Seljuk Turk stalactite style was added to that same Great Palace.

The very first minarets beside mosques were inspired by square

Syrian church towers, and there were other Christian elements that

influenced Islam. Prayer niches facing Mecca derive from east-facing

prayer niches of the early Christians, who also bequeathed Muslims

their prayer halls, prostration and fasting. Desert In the secular world the practice of secluding and veiling Muslim women was a straight lift not from the pages of the Koran but from the palaces of Byzantium, as was the harem. Indeed the caliphs' courts at Damascus and Baghdad inherited much of their love of luxurious costume, gold vessels, gorgeous gems and other indices of conspicuous consumption from the same spectacular source. As Lord Carey mentioned, Islam famously gave Greek Classical learning to the West – Aristotle, Plato, Euclid, Archimedes, Hippocrates – but Islam acquired it all from Byzantium, which for centuries had carefully preserved the precious inheritance in libraries of Antioch in Syria, Caesarea and Gaza in Palestine, and Alexandria in Egypt. Indeed, the citizens of Constantinople were accustomed to quote Homer much as we today quote Shakespeare. And in the ninth century the Caliph of Baghdad invited the Byzantine Leo the Mathematician to visit him, because Leo was a renowned expert on Classical science, mathematics and astronomy. A final irony. Ask anyone to name the symbol of Islam and you will be told, "A crescent". Why a crescent? Because when the Turks captured Constantinople they decided to adopt the city's symbol, a crescent moon, and make it their own. Thus, when turning St. Sophia into a mosque, they took the Christian cross off the dome and replaced it with their new emblem. The irony is that long before the time of Christ the city chose the crescent moon to honour Diana, a pagan goddess. Paul Bentley This article was first published in the Catholic Herald, 14 May 2004 The reconstruction of St. Sophia, Constantinople, is from www.byzantium1200.com |

All

content is copyright of © Mosaic Matters and its contributors.

All rights reserved

Mosaic

Matters is:

Editor: Paul Bentley

Web Manager/Designer: Andy Mitchell

At

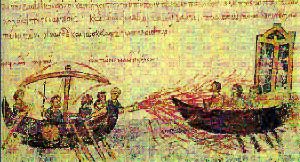

naval warfare however the Arabs were beginners. They had no fleet

and no experience, and it was Syrian sailors who provided crews

and know-how. The new boys in the Med learned quickly and soon won

sea battles, though the attack on Constantinople in 678 was defeated

by a Byzantine invention, flame-throwers spewing Greek fire, a weapon

the Arabs copied but never quite equalled.

At

naval warfare however the Arabs were beginners. They had no fleet

and no experience, and it was Syrian sailors who provided crews

and know-how. The new boys in the Med learned quickly and soon won

sea battles, though the attack on Constantinople in 678 was defeated

by a Byzantine invention, flame-throwers spewing Greek fire, a weapon

the Arabs copied but never quite equalled. Calvary

and environs loomed large in early Muslim architecture. The first

great Islamic building was the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, erected

to commemorate Mohammed's Night Journey. But it was inspired by

the Rotunda over the tomb of Christ, part of Emperor Constantine's

Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Hence the almost identical dimensions,

the central circular arcade and aisle, the dome and its windows.

The decoration too was Byzantine: marble and richly embellished

gold mosaic. Another great early Islamic building was the nearby

Aqsa Mosque. There the model was the part of the Holy Sepulchre

Church built over Cavalry itself, and the mosque again incorporated

features from Byzantine architecture. The Caliph responsible also

requested Byzantine help with the Great Mosque at Damascus and the

House of the Prophet at Medina, and the Christian Emperor of Byzantium

was happy to supply mosaicists and materials.

Calvary

and environs loomed large in early Muslim architecture. The first

great Islamic building was the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, erected

to commemorate Mohammed's Night Journey. But it was inspired by

the Rotunda over the tomb of Christ, part of Emperor Constantine's

Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Hence the almost identical dimensions,

the central circular arcade and aisle, the dome and its windows.

The decoration too was Byzantine: marble and richly embellished

gold mosaic. Another great early Islamic building was the nearby

Aqsa Mosque. There the model was the part of the Holy Sepulchre

Church built over Cavalry itself, and the mosque again incorporated

features from Byzantine architecture. The Caliph responsible also

requested Byzantine help with the Great Mosque at Damascus and the

House of the Prophet at Medina, and the Christian Emperor of Byzantium

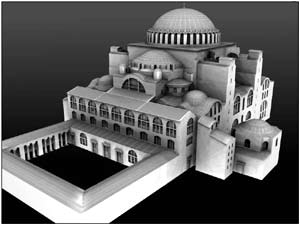

was happy to supply mosaicists and materials.  Undoubtedly

the biggest architectural challenge for Islam was to equal or surpass

the greatest temple in Christendom – St. Sophia in Constantinople.

Once the city was captured by the Turks in 1453 their architects

tried to do just that, and did indeed attain near-perfection in

the Blue Mosque, the Süleyman Mosque and others. Like Sophia

these glorious imperial buildings had a vast central dome supported

by semi-domes, an imposing porch and an arcaded courtyard with a

fountain for ablutions. But for all the perfection of Istanbul's

great mosques none of their domes ever exceeded the dome of the

mighty prototype.

Undoubtedly

the biggest architectural challenge for Islam was to equal or surpass

the greatest temple in Christendom – St. Sophia in Constantinople.

Once the city was captured by the Turks in 1453 their architects

tried to do just that, and did indeed attain near-perfection in

the Blue Mosque, the Süleyman Mosque and others. Like Sophia

these glorious imperial buildings had a vast central dome supported

by semi-domes, an imposing porch and an arcaded courtyard with a

fountain for ablutions. But for all the perfection of Istanbul's

great mosques none of their domes ever exceeded the dome of the

mighty prototype.  monks

used to chant psalms in the middle of the night, and this probably

gave rise to today's group chanting of the Koran by Muslims. In

fact Muslims were so impressed by the asceticism and other spiritual

practices of the monks that in due course they incorporated many

of these features into Sufi mysticism.

monks

used to chant psalms in the middle of the night, and this probably

gave rise to today's group chanting of the Koran by Muslims. In

fact Muslims were so impressed by the asceticism and other spiritual

practices of the monks that in due course they incorporated many

of these features into Sufi mysticism.