|

The Esther Benjamins Trust

When I was sixteen and contemplating which career path to follow, my older brother said to me, “You’re good at art; why don’t you become a dentist?” Bizarre advice to have offered - and perhaps even more curious was my decision to follow it. Thirty-one years later I’d still be on that not especially artistic course in life had it not been for the death of my first wife, Esther Benjamins, in January 1999. Esther took her own life, leaving a single-line suicide note explaining how her life without children had become “unbearable”. In the midst of all the emotions that the tragedy whipped up, I took a very clear decision to respond to that bleak note: I would cease being a British Army dentist and confront the childlessness by setting up a children’s charity in Esther’s name. I also decided that the charity would work in Nepal, the home of the Gurkhas, as we had enjoyed their company as neighbours before Esther’s death. Several years later, through the work of my unique charity, I was to rediscover my artistic roots and apply them in a more meaningful and rewarding way than the practice of dentistry. In 2002 The Esther Benjamins Trust was the first charity to identify and research the huge problem of Nepalese children who were being trafficked and sold by their families to Indian circuses. Ostensibly recruited as performers, the children were condemned to a punishing, exploitative working routine and a life of physical, psychological and sexual abuse. The average age of children joining the circus was eight or nine, but some could be as young as four or five. They would become de facto slaves and prisoners of the circuses, not seeing the outside world until their (illegal) contracts had expired. These could run for ten to fifteen years Having established the scale and nature of the problem, we set to work doing something about it. Since 2004 our workers have conducted dangerous visits to the circuses all over India – they are not there as admission-paying customers. Instead, they have gone, sometimes in the company of the police, and retrieved over 280 children from their misery. Once we have escorted them safely back to Nepal we cater for the returnees’ needs as their problems are far from over. An outcome of the daily violence that they endured throughout their captivity is that nearly all suffer some degree of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This can bedevil our attempts to help them pick up the pieces and lead some semblance of a normal, productive, family life. It is compounded further by the stigma that the girls have to endure after being seen to have been engaged in the lowly profession of “show girl”; few within their communities will offer a helping hand, least of all the treacherous parents who trafficked them in the first place. The girls’ lack of motivation (which has been beaten out of them) and education – accompanied by the aforementioned psychosocial problems - makes them virtually unemployable. It is too easy for these outcasts from society to find their way back to the circus (or worse) in their desperation. Our task has to be to provide not just the training – which in isolation can lead nowhere and waste resources – but also the jobs that these girls need. My own introduction to mosaics came in 2004 when I took a mosaic art holiday in Languedoc, France. The course involved the painting, characterisation and firing of plain white bathroom tiles and their use in the indirect mosaic technique. The appetite whetted, the following year I went on Martin Cheek’s summer course in Greece, and last year attended another of Martin’s courses in Tuscany. It was this very limited exposure that got me wondering if mosaic art could provide work for former circus girls. In October last year I set up a studio in my home just outside Kathmandu and began training two 16-year old girls, Rina and Priya. Their family backgrounds reflect the kind of difficult cases that we have to try to resolve: Rina’s mother is a prostitute, her father unknown. Both of Priya’s parents have committed suicide, a not unusual occurrence amidst the grinding poverty that is endemic in rural Nepal. Both girls came to the house every day and alongside my other charity duties I provided the designs, and, from my limited insight, the artistic supervision.

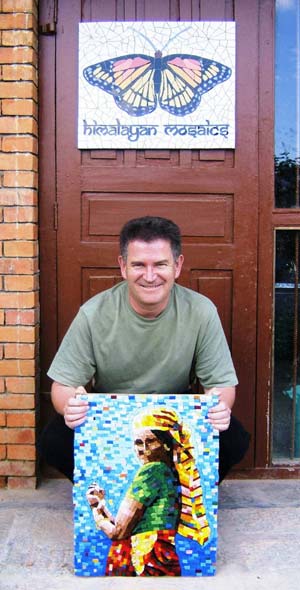

The girls displayed a real aptitude, so each month I would add another one or two girls to their number. There are currently 18 girls in the studio, producing beautiful works from locally-purchased bathroom tiles. Inspiration is drawn from subjects such as Nepalese flora, fauna and culture, Indian eighteenth-century court paintings, and from designs found in the exquisite carpets of Rajasthan. I marketed the initiative to charity supporters as “ethical gifts”; in return for a donation to The Esther Benjamins Trust supporters could commission a mosaic on behalf of themselves or friends. The completed work would remain in Nepal and they or their friends would receive a photograph or jpeg of it in situ at a children’s home, disabled children’s centre or school. A one foot by one foot mosaic would cost £50, take two days to make and the girl would receive £5 of that. A girl could therefore comfortably earn £50 a month which is an extremely good wage in Nepal. Rather predictably, supporters began to ask if they could get to own the mosaics. Out of this was born “Himalayan Mosaics”, a Nepalese not-for-profit company that I am currently registering. Girls will work to contract, giving them job security, and we will sell very affordable mosaics to the domestic and international markets. An indirect spin-off is the therapy that the art provides. I have had the huge privilege of seeing first-hand and on a daily basis the transformation of these brutalised young women (many of whom are rape victims) into laughing, positive individuals. Sometimes I hear them singing in the studio: the sweetest of sounds that never fails to give me a buzz. In my experience success is rare in Nepal and I can enjoy the most amazing of results literally on my own doorstep. However, I do have a wish list, which is the main purpose of writing this article. The cost of my charity’s operation seems to be growing exponentially and we have a matching need for general donations either up front or through a Will! Maybe a reader could help through selling a mosaic or through an exhibition for charity? Alternatively, we can always put surplus mosaic materials and equipment to good use.

We also have a need for volunteers in Nepal capable of offering training support in the arts in general and mosaic in particular. It would really be a great opportunity for any mosaic enthusiast to pass on their knowledge to the most willing and grateful of students. If that’s not possible even some design support from home would be well received. Mosaic art in Nepal is in its infancy; indeed my sole claim to fame is having introduced it to the country as there is no mosaic tradition here at all. With a little boost, now the infant can get to its feet and give a livelihood and hope to many other desperate girls.

Please visit our website to see more about The Esther Benjamins Trust: For any further information, please contact our London staff on 020 7600 5654 or by email: chris.kendrick@ebtrust.org.uk |

All

content is copyright of © Mosaic Matters and its contributors.

All rights reserved

Mosaic

Matters is:

Editor: Paul Bentley

Web Manager/Designer: Andy Mitchell