Scroll down the list for other articles.

A scheme to finish off Westminster CathedralApril 2010 Paul Bentley

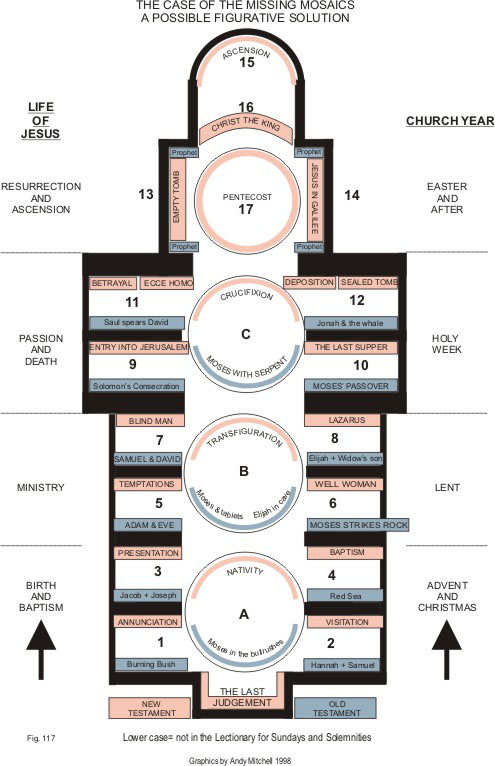

As you see, the plan starts at the extreme west end of the church with chaos, pre-creation, the pagan world before grace, and the effects of sin. The vaults that follow and first two domes of the main nave area are given over to the Old Testament: creation and the great covenants between God and Man. The third dome and the transepts are devoted to Christ’s work of redemption. The large tympanum above the sanctuary shows Christ the Almighty; and the sanctuary itself presents the Eucharist and the teaching of the Word, with Our Lady in the great apse at the east end.. This scheme was devised by Mgr Mark Langham, the former administrator of the Cathedral, Fr Aidan Nichols, a theologian, Prof. Eamon Duffy, a church historian, and Andrew Wilton, an historian of British art. Prof. Duffy explained that they wanted a scheme which was logical, and catechetical, and which reflected the structure of the Bible and the liturgy. My reaction to this scheme was that I hoped it wasn’t going to be the sole submission before receiving final approval. For example, why should the scheme be “catechetical”? That was the approach in the Middle Ages, when people couldn’t read. Nowadays being catechetical is a job for a catechism, catechists and the clergy; a cathedral’s task is to inspire worshippers with a sense of the glory of God. And in what way is this scheme “logical” if the Effects of Sin precede the Fall? Not to mention Plato, Lucretius, Buddha and Zoroaster. And giving two-thirds of the nave to the Old Testament means cramming the whole earthly life of Christ into the transepts. As for “reflecting the structure of the liturgy” the scheme completely omits Old Testament/New Testament parallels, such a prominent feature of Mass readings and indeed of church iconography over the centuries. And how does the Langham scheme embody the primary dedication of the Cathedral to the Precious Blood? Technically also domes of green, blue and red are heavy and oppressive (as in St. Paul’s in London and St. Louis in the USA), which is why Middle Byzantine domes principally used light colours and gold, with its astonishing ability to find the light. I append my own scheme for a mosaic scheme for the Cathedral. In contrast to the Langham scheme it is very much Christ-centered.

As for the idea that the mosaics ought to be catechetical, then

non-figurative Saint Sophia is a powerful rebuttal; that church

was its own iconography, so to speak; it was supremely a sacred

space. (If anyone had suggested to Emperor Justinian that the mosaicing

of Sophia was “just decoration”, he would have found

himself instantly posted to one of the remoter regions of the Empire.)

The gold ground of course contributed greatly to the sense of the

divine. I would also argue that a non-figurative “abstract” design can in itself be powerfully spiritual. I don’t mean designs with crosses and traditional Christian emblems, I mean the actual abstract design and its expression. Paul Bentley

|

All

content is copyright of © Mosaic Matters and its contributors.

All rights reserved

Mosaic

Matters is:

Editor: Paul Bentley

Web Manager/Designer: Andy Mitchell